The story of Champagne’s price-fixing “l’échelle des crus” system and how it was abolished

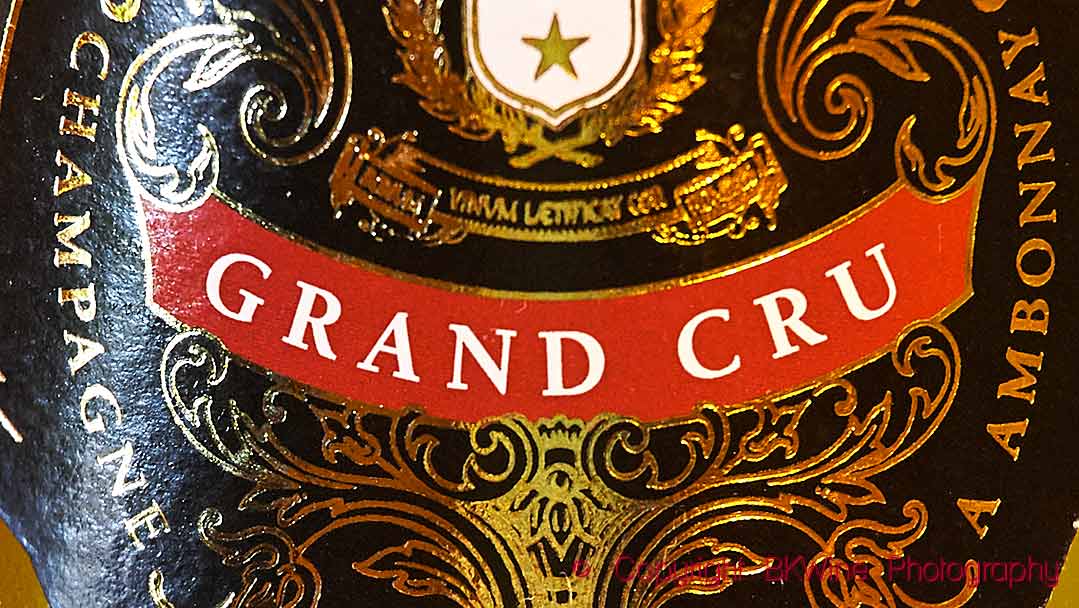

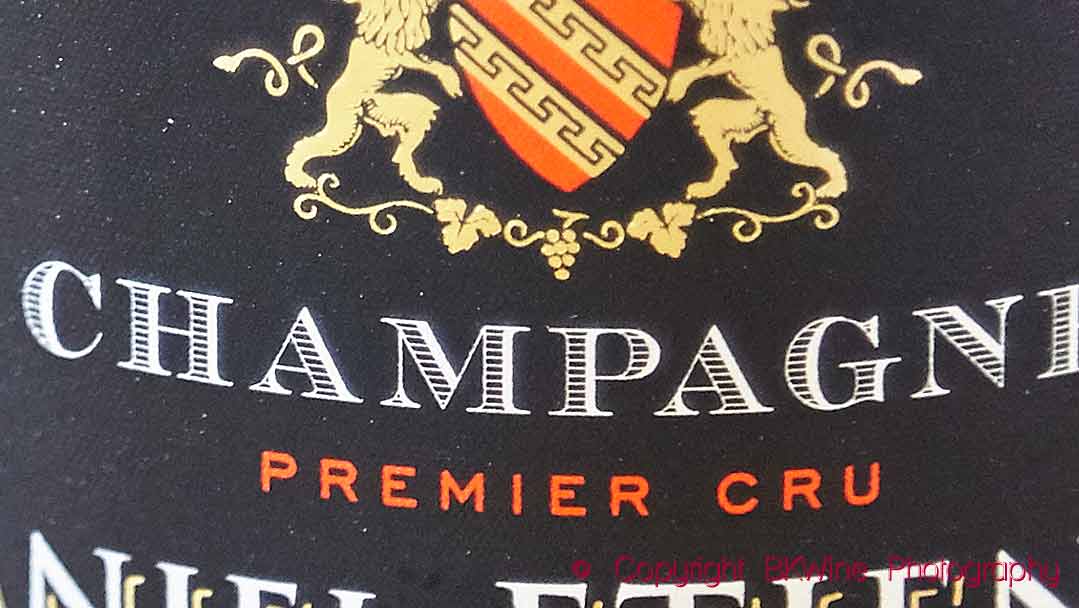

Grand cru and premier cru are famous words. You see them on many champagne bottles. Probably, most people take it as a sign that the wine inside is of better quality. Is that true? Not necessarily. In Champagne, these denominations were created mainly as a tool for price-fixing. Today, grand cru and premier cru has no official value; it is not an official quality indication, nor a classification. It is a historical mention that is still tolerated. To find the best quality champagne, you should look at who has made it, not what percentage it was given on a price scale a hundred years ago. Here’s the story, including some personal opinions on the evolution.

Still today, a lot of people talk about “l’échelle des crus” with its labels “grand cru” and “premier cru” in Champagne. You still see it a lot in wine media, hear it talked about by wine loves, even mentioned by champagne producers sometimes (quite often actually). Still today, twenty years after it was abandoned.

Grand cru, and premier cru, in Champagne, are historic denominations established in a system called l’échelle des crus. Today, it has been abandoned.

The cartel system

The system was created in 1919 as a tool to fix the prices of the grapes sold by Champagne grape growers to Champagne négociants (what is often called “Champagne Houses”), a sort of cartel system that eliminated free pricing. But even before this date, there were various attempts to classify the “quality” of different villages, or the grape prices, going back as long as to the 18th century. In 1919 it was established as a scale (échelle) that fixed the prices based on a central decision. We’re talking here about the price of a kilo of grapes.

This is a longer version of an article published on Forbes.com.

This was one of the results of a period in the late 1800s and early 1900s with a lot of conflicts on price, geographical limits, grape provenance and other issues in Champagne. There were, for instance, two violent Champagne revolts in 1910 and 1911, not only regarding grape prices though but mainly about geographical delimitations. The échelle des crus was one of the mechanisms put in place to try and calm tempers and regulate the market.

Update and clarification, 2023-05-19:

In 1911 a first scale was established, but it was not official and it was not followed very much (among other things, because of the small yields, 115 kg/ha in 1910 and 1600 kg/ha in 1911 – to compare with today’s around 15,000 kg/ha) . It was mainly unilaterally established by the grape buyers (the houses).

In 1919, representatives of the grape growers and the houses (buyers) agreed on a common scale. This scale was in and of itself not mandatory, but was nevertheless generally used in 1919-1925. In the following years, the way the scale was applied varied due to a crisis in champagne production. A compulsory minimum price was introduced in 1935 (via a décret-loi).

Grand and premier cru for central price fixing

With the échelle des crus system established in 1919, the “full” grape price was set centrally by decree, based on a central negotiation between some of the interested parties. Each village (or commune) was then given a percentage “score”, from a maximum of 100% and down. This eliminated any free pricing or price negotiation for the grapes between grape sellers and buyers. The price was decided centrally and applied for everyone.

Grape growers in the different villages – in the 33,000-hectares big wine region – were then paid a percentage of this full price, depending on what percentage had been attributed to their village.

The highest grape price was for grapes from a small number of villages given 100% of the centrally fixed price. These grapes were evidently considered the “best”. These lucky villages were given the name grand cru. One notch down in the percentage scale were the villages called premier cru, attributed to a larger number of villages. They were given a lower percentage of the price. Other villages, the majority of the region, had an even lesser percentage of the centrally defined price for the grapes, originally down to 22.55% of the full price (later revised upwards).

Over time, some villages were promoted, moved up to a better group, up to premier cru or grand cru. The number of “cru villages” increased. There are now 17 grand cru villages and 42 premier cru villages.

The cru-system evolves

As time passed, the percentages also changed. Initially, the lowest percentage was 22.55%, and the maximum 100%. Those poor growers at the bottom did not get a lot of francs for their grapes. At the end the life (I’m coming to that soon) of the system of l’échelle des crus, the lowest percentage given to any village was 80%. The vast majority of Champagne villages were in the range 80-89%. The next level up from that, 90-99% villages, were premier cru. The 100% villages were grand cru. These percentage ranges were set in 1952 and were used until the end. Some changes in village rankings were, however, made.

An additional regulation, introduced in 1962, stated that growers were not allowed to plant pinot meunier in villages ranked 96-100%, so no new plantings of pinot meunier in grand cru nor in some of the premier cru (96% or higher).

The price-fixing is abandoned, the cartel disintegrates

With time, this system with a centrally controlled price of a commercial good (grapes) traded between independent commercial entities (grape growers and négociants), the cartel, became increasingly contrary to the European Union’s fundamental principles of open and free markets and its anti-trust regulations. It became increasingly clear that this kind of anti-competitive rules would have to be abandoned.

The central price-fixing with the échelle des crus system was therefore abandoned in 1990, but the scale still remained in place, but without the centrally controlled pricing.

But still after this, the CIVC kept for some time a “ghost” of the price-fixing system by announcing an “indicative” price. This was in place until 2001, when it too was abandoned, following EU rulings that centrally indicative prices were also incompatible with a free and fair market (a ruling prompted by that several regions, not only Champagne, practiced such “recommendations”).

A little later, in 2004, the échelle des crus itself was abandoned. (What purpose could it possibly serve?)

With this, the pinot meunier restrictions have also been removed. (Today there are seven “grape varieties”, soon eight, permitted in Champagne, read more here.)

Grand cru and premier cru as a historical remnant

Since 2004, when it was abandoned, Champagne’s denominations “grand cru” and “premier cru” have no official value.

The words can still be used, but they are not a classification, nor quality or price ranking. They are tolerated, can still be used, “by virtue of local, loyal and constant customs”, “en vertu des usages locaux, loyaux et constants” as the French legal text puts it.

The villages allowed to use them are defined in the government décret (see at the end of the article).

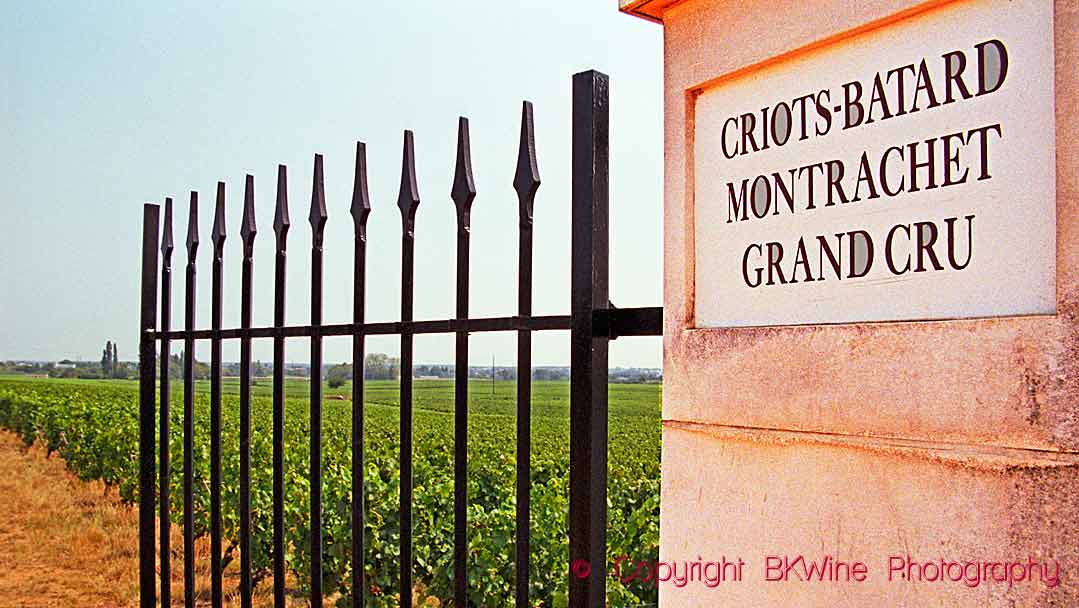

This is fundamentally different from how grand cru and premier cru is used in other wine regions in France, where they still have an official value. There are essentially two different uses of it:

As an appellation

In, for example, Burgundy, grand cru and premier cru is part of the appellation system. There are certain areas (vineyards) that are classified as grand cru, for example, “grand cru Chambertin”. Each of these has their own appellation protégé (AOP/AOC), 33 in total. (As a comparison and in contrast, Champagne is one single AOP.) This is a strict geographic delimitation of what is often considered the best plots. Similarly, premier cru is a second level of vineyards, also a part of the appellation system. The appellation rules controls the use of grand/premier cru and also defines numerous other rules for each appellation (yield, grape variety and much more).

In a few other regions, there are similar uses of the word for certain appellations, for example Quart De Chaume Grand Cru in Loire or Alsace Grand Cru.

As a classification

In Bordeaux (and Provence), these words are used as “classifications”, for example, “premier grand cru classé”. This has no direct relation to the appellation system but is a curious system that, according to the creators of the different classifications, attempts to rank specific wineries. There is generally not any specific link to the actual plot (vineyard) but is generally a classification of the winery’s name, or the “brand”. The “original” classification, the 1855 Classification, was simply a ranking based on price.

The value of these classifications is hotly debated, or questioned, today. In practice, they seem more to serve as a barrier against competition created by those who are “inside” against those “outside” and as a way to extract higher prices from consumers. They don’t really serve much of a purpose as a quality indicator for the consumer.

The grand and premier cru in champagne was never an appellation or a classification in these senses, but simply a structure – a scale – put in place to define the prices.

This also highlights the fact that an appellation is quite different from a classification. It is easy to confuse the two, but they are fundamentally different animals. The appellations are geographical denominations, with numerous additional rules defining the appellation. A classification is an attempt to a ranking of estates (or brands) based on sometimes arbitrary factors and usually not directly related to a specific geographic plot of land (vineyard), in other word it is (mostly) not a vineyard that is classified but a name.

So, in essence, there are three different uses of the words grand and premier cru:

- as a sentimental and historical indication in Champagne,

- as a qualifier of an appellation, i.e. a specific plot of land, for example, in Burgundy’s grand and premier crus appellations, and finally

- as an attempted ranking of wineries/wine brands, as in the various Bordeaux classifications

Any other use is forbidden and can be punished by law.

Grand and premier cru in champagne today

Today, the main “value” of grand cru and premier cru is that the growers who are fortunate to have vineyards in those villages may be able to extract a higher price for their grapes and often can extract higher prices from the consumer for the thus labelled wines, without necessarily providing a better quality product (the wine is “automatically” more expensive with those two words on the label).

Yes, of course, those villages often produce good and excellent fruit and wines, but that they by definition are better than those who don’t have the right to those names is simply not true. Today you can find outstanding top-level champagne that is not grand or premier.

But there is still a lot of prestige connected to the two denominations.

Today, you can find top-quality champagne in all parts of champagne, disregarding if you can find the words premier or grand cru on the label. It is to a much greater extent the talent of the vine-grower and the winemaker that decides the quality of what you have in the bottle.

Don’t let smoke and mirrors, or bling-bling, be what decides which champagne to drink.

Choose your champagne based on the producer or based on what you taste, not on a historical text on the label.

All champagne grand cru

Grand cru is allowed for the following 17 villages:

- Ambonnay *

- Avize *

- Aÿ *

- Beaumont-sur-Vesle *

- Bouzy *

- Chouilly

- Cramant *

- Louvois *

- Mailly-Champagne *

- Le Mesnil-sur-Oger

- Oger

- Oiry

- Puisieulx

- Sillery *

- Tours-sur-Marne *

- Verzenay *

- Verzy

(They can also use premier cru if they want.)

The asterisk (*) indicate the eleven villages that were grand cru on the 1919 list.

All champagne premier cru

Premier cru is allowed for the following forty-two villages:

Avenay-Val-d’Or, Bergères-lès-Vertus, Bezannes, Billy-le-Grand, Bisseuil, Chamery, Champillon, Chigny-lès-Roses, Coligny (Val-des-Marais), Cormontreuil, Coulommes-la-Montagne, Cuis, Cumières, Dizy, Ecueil, Etrechy, Grauves, Hautvillers, Jouy-lès-Reims, Ludes, Mareuil-sur-Ay, Les Mesneux, Montbré, Mutigny, Pargny-lès-Reims, Pierry, Rilly-la-Montagne, Sacy, Sermiers, Taissy, Tauxières, Trépail, Trois-Puits, Vaudemanges, Vertus, Villedommange, Villeneuve-Renneville, Villers-Allerand, Villers-aux-Nœuds, Villers-Marmery, Voipreux and Vrigny.

This is a much-simplified history of the hundred years of existence of the échelle des crus. It is to a large extent based on this excellent description: “L’échelle des crus en Champagne” by Jean-Luc Barbier.

Here you can find the official decree: Décret n° 2010-1441 du 22 novembre 2010 relatif à l’appellation d’origine contrôlée « Champagne », cahier des charges de l’appellation d’origine contrôlée « champagne ».

Travel

If you want to discover some of the very best champagnes, including some grand and premier crus and champenois gastronomy, you can come on a wine tour to Champagne with BKWine.

Travel to the world’s wine regions with the wine experts and the wine travel specialist.

Grand wine tours. BKWine wine tours.

Read

If you want to know more about champagne, and find some of the best growers, then you can read our very extensive book on the region: Champagne, the wine and the growers. (Unfortunately only available in Swedish currently.)

One Response

I’m a wine educator in the US and I am researching the echelle des crus. I have a couple very detailed questions that only someone like Jean-Luc Barbier may be able to answer. Do you happen to have an email address for him that you are at liberty to share?